Gold as Archive: Kurdish Women, Memory and Survival

Among Kurds, zêr (gold) is less a luxury than a portable archive. In a landscape marked by migration, shifting borders, and repeated wars, gold has functioned as both a flexible store of value and a silent passport. During the Anfal campaigns, the Iran-Iraq War, the embargo years of the 1990s, and the ISIS offensives, families repeatedly converted bracelets and coin belts into bus fare, rent, or seed money to rebuild. Unlike cash that inflates or bank accounts that vanish with regime change, high-karat gold can be weighed anywhere. A bent bracelet trades the same as a pristine one; beauty is beside the point when survival is the currency. The metal itself is the guarantee.

Gold as a Lifeline

This practicality sits alongside a deep ethic of inheritance. Gold is gifted to daughters and daughters-in-law at weddings, pinned to garments by relatives, and remembered in families piece by piece, gram by gram. Mothers teach daughters which clasps are most secure, how to read hallmarks, and when to sell only the chain but keep the coin. A typical Kurdish trousseau includes coin necklaces, bangles, and sometimes the iconic Kamar belt - a must-have dowry or gifted piece, chosen because it is recognisable in the wider Middle Eastern marketplace and can be exchanged quickly in hardship. The result is a matrilineal safety net: wealth a woman controls on her body or in her jewellery box, ready for emergencies but intended also for the next generation.

Marriage customs make this explicit. Under Islamic law, the mahr (bridal gift) belongs solely to the bride; in Kurdish practice, gold often makes up a large part of this endowment. Community gifting at weddings further augments her holdings, creating a starter portfolio she can use for household needs, medical crises, or business ventures. While the Western world often collapses these customs into the word dowry, the Kurdish system emphasises assets under the woman's control - her tangible lifeline.

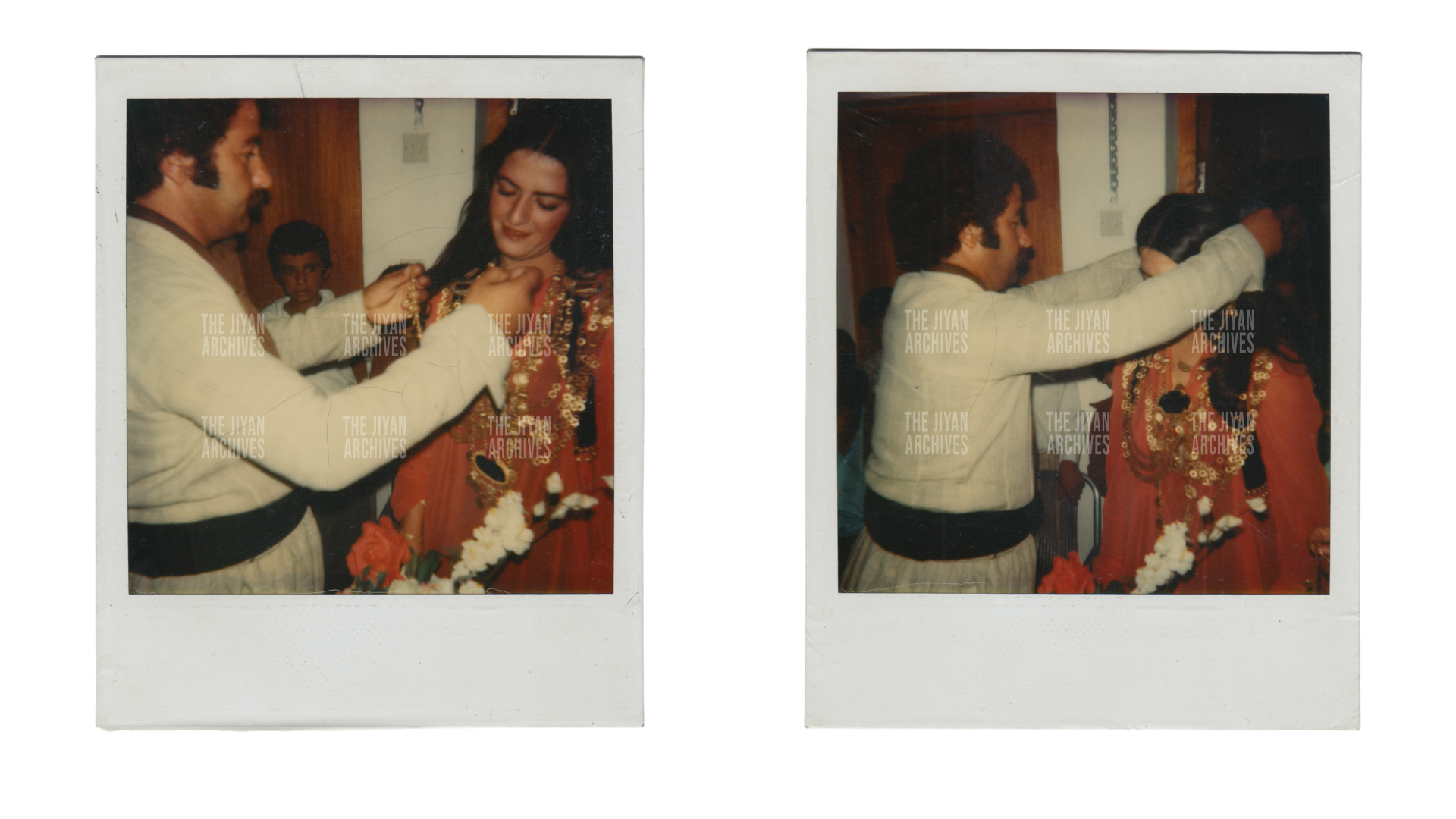

The gifting of a Kurdish bride’s gold from her newlywed husband. 1982, Slemani, Kurdistan - Raz Xaidan Archives (img_0235/0236)

As I've gotten older, I've come to see the value of gold jewellery much more than I did when I was younger. During gatherings with family and friends, when women sit over tea and trays of sweets, the topic inevitably turns to gold. They reminisce about how, in the 1990s and early 2000s, they helped one another bring gold from Kurdistan, becoming each other's trusted couriers for such precious cargo. They laugh about how they once bought so much with so little, and how they wish they had purchased more before prices soared. Their excitement is infectious. Someone always has a new piece to show - a bracelet, a necklace, perhaps a new ring, and the conversation fills with admiration and memories of first purchases. Younger women talk about saving enough to buy lira coins for their children, so that one day those coins can be turned into jewellery of their own. The older women nod approvingly, offering the same refrain heard in Kurdish homes for generations: You can never go wrong with gold.

I remember my first gold piece vividly: a necklace my parents bought me with my name written in Kurdish. The weight of it against my collarbone felt significant, grown-up. I was beyond excited- feeling mature and connected to something much larger than myself. I watched my mother's careful hands fasten the clasp, the same hands that had fastened her own mother's jewellery decades before. That necklace was more than an adornment; it was an initiation into an unspoken inheritance, a claiming of my place in a long chain of women who understood that beauty and security were never separate things.

Kurdish Jewellery: Forms, Regions, and Cultural Signatures

The Kamar Belt - Wealth at the Waist

The Kamar belt, worn around the waist at weddings and celebrations, is one of the most recognisable Kurdish adornments. Crafted from linked coins or engraved gold panels, it symbolises prosperity and strength. Its placement- around the body’s centre- marks it as both decorative and defensive, a visible promise that a woman’s wealth travels with her. Over the years, the style has evolved from flower patterns to broad squares and three or five-piece sections with Lira clasps. Many families still measure security in the weight of the Kamar belt, knowing it can be traded in as one of the best investments.

Kurdish bride is being gifted gold at her wedding, followed by an embrace. 2023, Germany - Kashma Djaf Archives

The Ashêqbend: Promise and Protection

The Ashêqbend, which beautifully translates as “the binding of love,” is a common bridal piece that literally and symbolically binds love to the body. Commonly formed of three filigree gold pieces: two resting on the shoulders, and one pinned delicately at the lower chest. Each piece connected by delicate ringlets of gold, threaded together into a light, shimmering chain, catches the light like a glowing gesture. The origins of this piece are believed to lie among Amazigh communities and were later embraced by Kurds. Traditionally gifted to a new bride during engagements, brides often chose it as a statement of promise and protection. Balancing aesthetic grace with intrinsic value - It is a beauty that can, if needed, be broken down and sold without losing meaning. It represents love not only as a sentiment but as security. The Ashêqbend remains one of the most intimate pieces of Kurdish jewellery.

Kurdish women photographed in the 1990s wearing traditional dress and gold jewellery. Duhok, Kurdistan - Dilman Yasin Archives

The Sar Parcham: Form, Power & Continuity

One of the most iconic examples is the Sar Parcham - a decorative charm (often moon-shaped) used in Kurdish jewellery (earrings, necklaces, chains) and in adorning Kurdish garments. More than decoration, it is a declaration of heritage, uniting gold’s permanence with the vitality of colour. The Sar Parcham appears everywhere: suspended from earrings, dangling from forehead chains (sarpêç), adorning the edges of traditional dresses, hanging from wedding headdresses. Its form varies - some crescents are simple gold curves, others are elaborate constructions featuring filigree, colored stones, or tiny coins. But the function remains constant: it marks the wearer as Kurdish. More than an ornament, the Sar Parcham operates as cultural technology. In diaspora, it signals identity without words. At weddings, it connects brides to maternal lineages. In markets, its presence confirms authenticity - a piece may be old or new, heavy or light, but if it bears the Sar Parcham, it speaks a Kurdish visual language that needs no translation. While closely associated with Kurdish dress, similar crescent forms and charms also appear in Assyrian adornment traditions, reflecting shared regional aesthetics and long histories of coexistence.

Ottoman and Turkish Lira Pieces

Walk through any Kurdish gold market, and coin jewellery dominates the display cases. Ottoman gold liras, Turkish Cumhuriyet coins, even British sovereigns - mounted as pendants, strung into necklaces, or framed as earrings. The logic is immediate: coins are standardised, their weight and purity guaranteed by the state that minted them. No need for lengthy negotiations when gold must become cash. The decorative bezels that frame these coins often feature the Sultan's tughra, an elaborate calligraphic signature of the Ottoman Empire.

The evolution of the adorned Sar Parcham from brass to gold, and the Ottoman ‘Lira’ gold coin that remains a staple in worn jewellery.

Southern Kurdistan (Bashur): Stone and Symbolism

Cross into Southern Kurdistan, and the palette explodes. Here, colored stones aren't merely accents - they're central to the design language. Carnelian reds, turquoise blues, jet blacks, and emerald greens punctuate heavy gold chains and pendants.These aren't precious gems in the Western sense; most are semi-precious stones chosen for their symbolic resonance rather than market value. Green for Kurdistan's mountains, red for vitality and the blood of martyrs, blue for the Tigris and Euphrates carving through ancient valleys. A necklace becomes a chromatic map, anchoring the wearer to a specific landscape of memory and belonging. In Kurdish adornment, cloves appear alongside gold and stones as quiet talismans believed to ward off harm and invite abundance. The Xhêl û Mêxhek necklace combines large, flattened stones like carnelian for vitality or onyx for grounding, with cloves on the adjacent sides. Designed for both everyday and formal wear, the Xhêl û Mêxhek is a traditional Kurdish necklace that combines adornment with fragrance.

The colours and shapes of stones featured in gold items from Southern Kurdistan. Photo: The Jiyan Archives

Northern Kurdistan (Bakur): The Filigree Tradition & Mythology

In the north, particularly Mêrdîn and Amed, the telkari tradition of Upper Mesopotamia reaches its finest expression. Filigree work - delicate wirework that seems to float above the gold's surface, adds intricacy without adding weight that can't be reclaimed at resale. Kamar belts, bracelets, and wide cuff bangles (bazin) showcase this technique best. The gold forms geometric patterns - stars within hexagons, floral spirals that echo tilework from Amed's mosques, but the skill lies in maintaining structural integrity while minimising gold use. Beauty emerges from craft, not mass. The Shahmaran motif appears frequently here, the snake-woman of Kurdish legend, half-human, half-serpent, associated with wisdom and healing, a native of Bakur. She winds through pendants and dangles from earrings, a pre-Islamic symbol that survived by adapting, much like the Kurdish people themselves.

Eastern Kurdistan (Rojhelat) and Diaspora: Yazidi and Assyrian Influences

In the Rojhelati regions of Kurdistan and among diaspora communities, jewellery often incorporates motifs from Kurdistan's religious minorities- particularly Yazidi and Assyrian Christian traditions. Peacocks - sacred to Yazidis as representations of Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel, appear as delicate engravings or repoussé work on gold pendants. Rosettes and solar symbols, drawn from ancient Mesopotamian and Assyrian heritage, connect contemporary wearers to civilisations that predate Islam by millennia. These pieces speak to Kurdistan's role as a refuge for religious diversity, where gold becomes a medium for preserving endangered traditions. Pomegranate motifs cluster particularly in these eastern styles - symbols of abundance, fertility, and the unity of diverse peoples (many seeds, one fruit). They appear as dangling charms, engraved details on bangles, or three-dimensional forms on earrings.

Filigree and folk motifs shape gold from Rojhelat & Bakur, drawing on nature, craft traditions, and regional symbolism.

Male Makers, Female Custodians

Kurdish gold sits within a larger Middle Eastern conversation about marriage, security, and female property. In Iran, brides receive Bahar-e Azadi bullion coins; in Turkey, guests pin Cumhuriyet altınları at weddings; in Egypt and the Levant, lira bangles and coin bracelets play the same role as Kurdish belts. Among Amazigh women in Morocco, silver jewellery holds parallel value as both portable wealth and identity, though silver there carries stronger spiritual associations. Across the region, what outsiders mistake for ornament is often a family’s emergency fund. Paradoxically, a tradition so closely tied to women’s security has long been shaped by male-dominated networks. Goldsmithing and retail have historically been men’s domains - bazaar guilds and wholesalers setting purity standards, weights, and fashion cycles. Their priorities encouraged the prevalence of coin jewellery and standardised bangles. Yet women continually reshape the canon, commissioning custom filigree, reviving heritage headpieces like the Sar Parcham, or mixing heirloom coins with modern chains.

More Than Ornament

Worn on the wrist or waist, tucked into a dowry chest, or quietly sold to bridge a bad season, Kurdish gold is an archive you can carry: of family bonds, regional craftsmanship, vibrant colours, and the enduring determination to turn beauty into security. Kurdish gold endures because Kurdish women endure. What we wear is not simply metal; it is memory forged into form. It carries the fingerprints of mothers who quietly saved, the breath of brides stepping into new lives, and the resilience of families who rebuilt after every displacement. Each piece, whether a coin necklace, a Shahmaran pendant, or a simple nameplate, holds a story that outlasts borders and outlives regimes.

In a world that has asked Kurdish women to be both soft and unbreakable, gold has been our companion: our inheritance, our safety net, our witness. We pass it down not only for its worth, but for the reminder it carries that no matter where history scatters us, we are never without a piece of home.