Alevi Women as the Keepers of Memory: Jin Heq e, Jin Heqîqet e

Haq = Truth, God Heqîqet = Ultimate truth

A Faith Carried, Not Written

Alevism is a faith tradition found across Kurdistan, Turkey and the Zaza regions, which follows its own practices, ethics, and spiritual worldview rooted in community, music, and oral tradition. Since Alevism developed across different ethnic groups, its identity can feel complex - shaped by language, history, and the experience of surviving alongside dominant cultures. Its continuity has depended not on institutions, but on people - on practices passed hand to hand, voice to voice.

In Alevism, Haq is not separate from humanity. We are Haq, and Haq is us - inseparable from all living beings. Alevi cosmology honours a foundational principle: equality. Women and men are equal reflections of divine truth, not symbolically, but in lived reality. Knowledge (irfan) and experience (hal) are not granted by textual authority, but recognised in those who embody Haq through their lives and rituals.

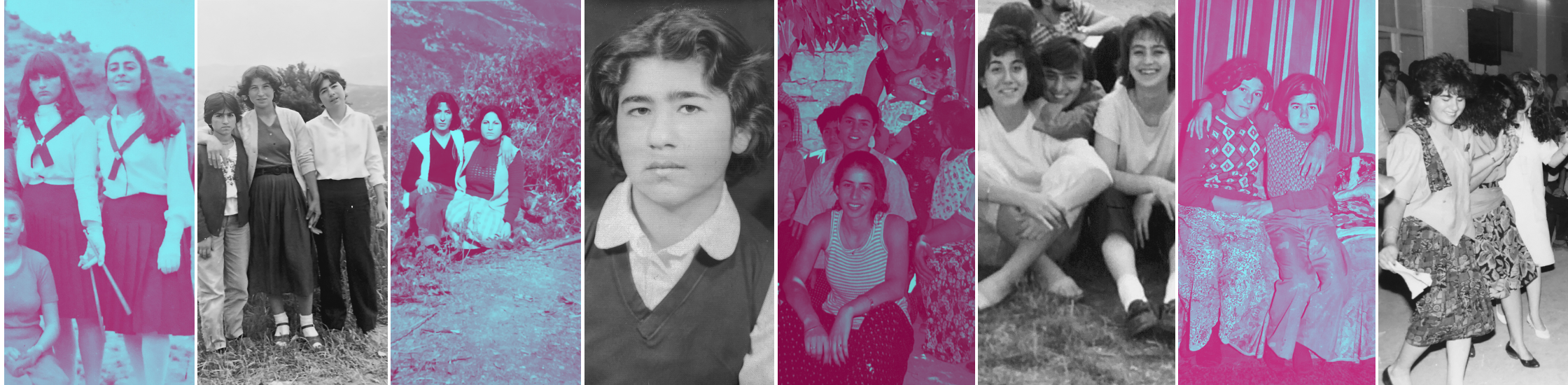

Together outdoors, a family of Alevi women and girls sit together in Mêrsin, Erdemli . The photograph was taken in 1995 - Toprak Archives (0303)

A family of Alevi girls and women gathered for a group photograph in Marçik, capturing generational presence and kinship,1988 - Rosa Jiyan Archives (0309)

Remembrance as Resilience

Since Alevism was (and still is) marginalised due to historical, political and social factors, Alevism was practised in secrecy. Alevis continue to face discrimination and exclusion from the Sunni majority society in Turkey and Kurdistan. The Turkish government historically refused to grant Alevis recognition and rights, causing persistent obstacles to religious freedom, and the political situation in Turkey has not provided a conducive environment for meaningful change. While the Alevi community fought (and continues to do so) for equal treatment and recognition, women became ‘oral historians’ ensuring the community’s collective identity survived state oppression, forced assimilation and displacement. In Alevi ethics, “unutmamak” (to not forget) and in Kurdish, “em ji bîr nakin” (we do not forget) is a moral duty, particularly to remember and honour the souls (can) lost from the atrocities committed against both Alevi and Kurdish communities.

In 1981, Alevi girls who had cut their hair short together in defiance, marking a shared moment of youth and self-expression, Dêrsim - Rosa Jiyan Archives (0306)

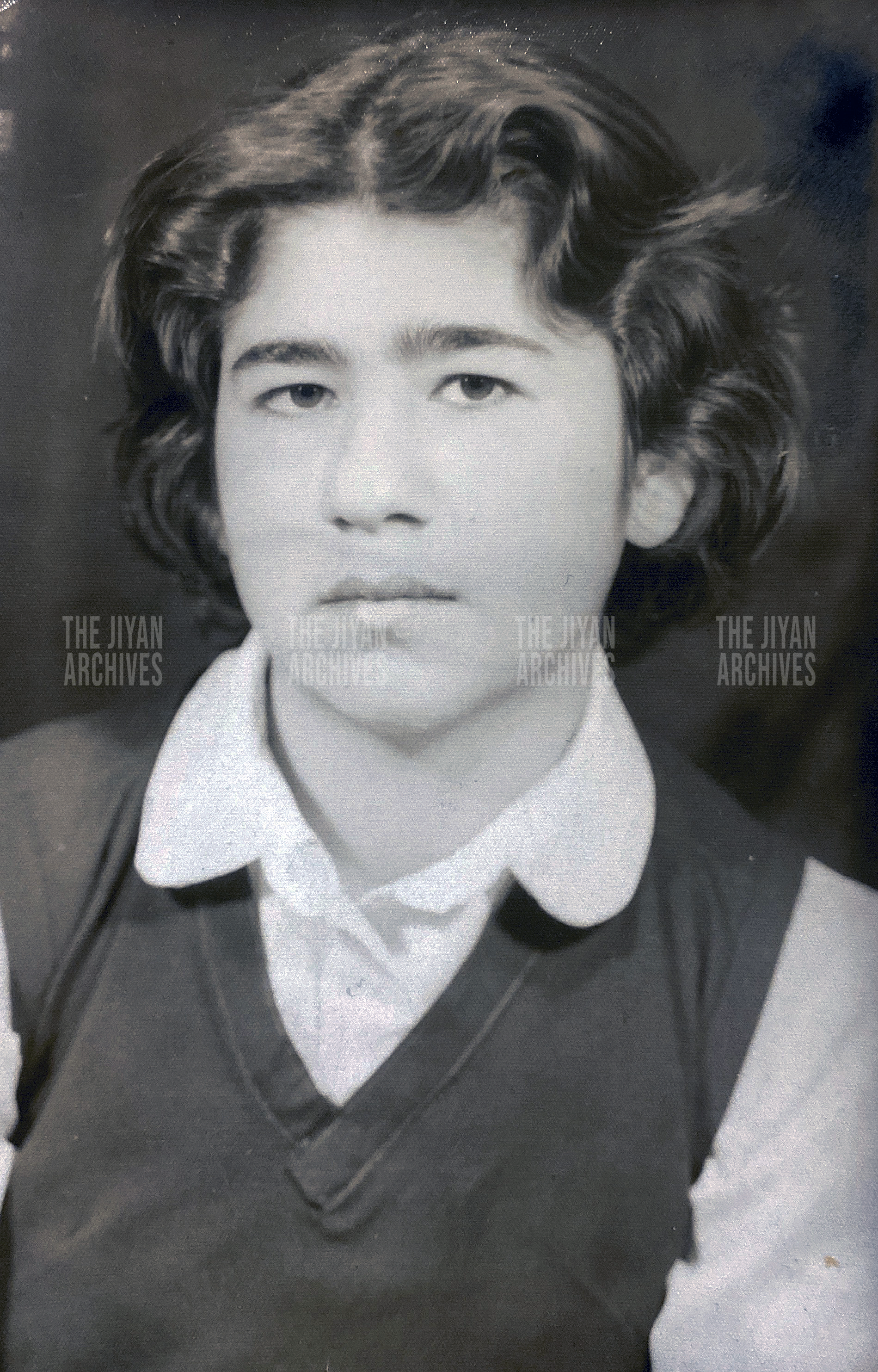

A passport photo of an Alevi girl, taken in Dêrsim,1979 - Rosa Jiyan Archives (0304)

Kurdish and Alevi history has adapted to external pressures (such as colonisation, patriarchal state violence and assimilation) by relying on the practice of oral traditions. The transmission of knowledge, values, identity, and beliefs has predominantly occurred this way to ensure that this cultural heritage remains alive. The preservation of Kurdish Alevi traditions has been thanks to women; they have acted as keepers of memory and become living archives of our communities. The role of Kurdish Alevi women as the keepers of memory runs deep into both the spiritual and cultural heart of Alevism. Their roles extend beyond the social and familial; they also encompass ritualistic, poetic and cosmological duties. In many Alevi Kurdish communities, especially in rural areas, women have historically played an essential role in transmitting oral traditions through songs (deyiş), (nefes), laments (ağıt, bend), and stories of ancestors.

During a local gathering, Kurdish Alevi women dance halparke, forming a connected line of movement and sound in Dêrsim - Rosa Jiyan Archives (0313)

Dêrsim girls seated on the grass at ODTÜ University in Ankara, captured in 1988 during everyday campus life- Rosa Jiyan Archives (0307)

Women and the Practice of Justice

In Maraş, Alevi women known as zakire - from zakir, meaning “one who remembers”- perform cem ceremonies alongside male zakir. Considering Alevism has been heavily assimilated, it is very important that these women zakire recite nefes in Kurdish as resistance to erasure and state assimilation. Among Kurdish Alevi female figures, one name holds particular significance: Elif Ana (1908-1991). Elif Ana is significant to Alevi Kurds of the Maraş region because she embodied Haq through her life and devotion to values such as love, peace, equality, and humanity. She remained faithful to the values and rituals of Alevism, for every guest she hosted, there were heartfelt conversations, gatherings, songs, and semah (Alevi dance/ritual) during cem ceremonies. After the Maraş massacre, Elif Ana became a symbol of Alevism and resilience; she remains a sort of saint or mentor to Alevi people, and her shrine is visited by many for various reasons. In Dersîm, women known as Ana Baci/Bacê preserve the stories of Alevi poets and saints, as well as the lived accounts of the Dersîm genocide. Often, these women perform laments (ağıt) that incorporate historical trauma and sacred cosmology. For example, the grief of genocides towards Alevis is woven together with the grief of the loss for those killed in Karbala, Iraq. This serves as a symbolic reminder of religious injustices, a sorrowful past and resistance towards perpetrators.

The Alevi concept of justice, grounded in principles such as equality (eşitlik) and consent (rıza), along with the moral imperative to walk the path of truth, intersects with the Kurdish women’s movement. The commitment to strong ethical foundations, emphasis on accountability, communal harmony and resistance to tyranny is also reflected by Alevi Kurdish women such as Zarife, emblem of the Kurdish Koçgiri resistance, Sakine Cansiz, the co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Bese Hozat, co-chair of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK); their lives throughout history demonstrate that justice is not only a spiritual ideal but a tangible commitment. Zarife emerged as a defining figure of the Koçgiri rebellion, embodying Kurdish Alevi women’s direct participation in resistance against Ottoman rule. For Cansiz, she connected her mother’s oral teachings and cem-like communal ethics to her political consciousness. Her Alevi background shaped her fierce sense of moral integrity and defiance, her resistance in prison, her critique of male authority, and her commitment to women’s autonomy, all of which reflect a justice ethic rooted as much in Alevi spirituality as in revolutionary praxis. Similarly, Bese Hozat articulates justice through a lens that merges Alevi humanism with the Kurdish movement’s vision of democratic confederalism and gender liberation, arguing that true freedom requires the transformation of both inner ethical life and external power structures.

Truth Is Lived

A sorrowful narrative of Kurdish Alevi identity has emerged from a past of massacres, executions and discrimination. However, amidst that sorrow, you find resilience, love and community. Alevi women’s memory work reflects the belief that truth, Haq and Haqiqet, is not written, but lived – carried in breath, song and love. The interwovenness of this ensures that a song can carry centuries of culture and survival. Women have always been, and continue to be, the driving force of the Alevi faith. Despite persistent efforts by patriarchal societies and male-dominated religious structures in the region to erase Alevi women’s agency, they have actively resisted marginalisation and ethnic cleansing, reclaiming space in both religious and private spheres and ensuring that their voices and leadership shape the core of community life.

On the path of truth in Alevism, there is no hierarchy, discrimination, or exclusion. Alevi women have sustained this ethic across generations, ensuring that love, justice, and collective responsibility remain lived principles rather than abstract ideals - they continue to exist with love and resilience.

Kurdish Alevi friends gathered in the fields of Marçik during a festival in 1982. One girl holds drumsticks, marking the occasion, Dêrsim, Kurdistan- Rosa Jiyan Archives (0312)